Six Degrees of the Civil War: Tintype Photographs in the Digital Age

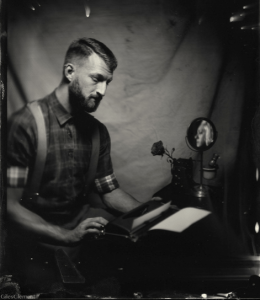

In December of 2015, Philly.com’s staff writer Jeff Gammage caught on to a photography trend taking the urban hipster world by storm: the revival of 1860s tintypes. Tintype pictures of average people, well-known folk singers, and even Kevin Bacon from cutting edge dark rooms are fetching high prices. Gammage referred to this art form, practiced by Newport Folk Festival photographer Giles Clement, as “the steampunk of photography.” Steampunk fans re-envision the Victorian past and blend it with modern technology, out of a combined sense of nostalgia for a fictive, smoky-lensed nineteenth-century and a fascination with real antiques. The steampunk movement is often intentionally more fanciful and creative than steeped in history. So why, we might ask, is the medium associated with Civil War battlefield photographers Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner now evolving into a fascinating Gen. Y art movement?

Most Civil War enthusiasts are familiar with the tintype, a nineteenth-century photo technique that captures an image on a metal plate. The method was developed by Adolphe-Alexandre Martin in 1853 as a successor to the ambrotype and daguerreotype and used the same wet-plate collodion process to create an image through light exposure. This great video from the Smithsonian explains how a tintype was designed during the 1850s-1880s. The subject sat for a few minutes, and the entire process took approximately fifteen to complete. Tintype photography was quick and inexpensive, which led to its rise in popularity. Tintypes fell out of style with the evolution of newer, quicker photography techniques…or so the past generation of photographers thought.

Contemporary tintype photo shoots are nothing new. Civil War reenactors and Steampunk fans have been sitting for their own portraits for decades as a way to recreate the past. The difference this time, according to Gammage, is that tintypes are appealing to a larger audience of artists, musicians, and people simply curious about the process of taking a non-instant photograph. In our hipster age of “slow food” and the return of handcrafted products, modern tintype enthusiasts seek imperfect, yet skillfully crafted images, looking for an art form that is timeless and requires patience to develop. We have all seen pictures of dower-looking Victorians and wondered what it would be like to sit in one pose for several minutes to take a photo. Why not experience it ourselves?

A small group of photographers is leading this vintage charge; these include Clement, John Coffer, a traveling photographer who hosts students at his Camp Tintype each summer; Victoria Will, who shot celebrities like Bacon at the Sundance Film Festival; and Rob Gibson, who made my own tintype photo (shown below) in Gettysburg a few years ago. Others have also been bitten by the 160 year-old bug, and unlike those old-timey boardwalk photography studios that add sepia tones to digital photos in an attempt to manufacture age, these artists are the real deal. Most use authentic nineteenth-century cameras to shoot their subjects.

But what is the main force behind this new interest in this Victorian-era Polaroid? First and foremost, unlike our digital-age photos, which can be reproduced and retouched with Photoshop, tintypes are only made once. What you see is what you get. The process requires specialization. While anyone can use Instagram filters to beautify images, few know how to take and develop a physical photo, and an even smaller number of photographers are capable of doing so using technology from the mid-1800s. The artistry of the tintype process appeals to our sense of nostalgia. In a world in which images appear and disappear in a second, the tintype allows people to return to an era when photographs were novel and lasting. Taking a tintype connects us with the past in a way that feels grounding, like listening to a favorite song from high school. Like reenacting, sitting for a tintype allows you to feel connected to those who did so more than a century ago. It feels authentic.

Plus, they look pretty cool, too.

Sources:

Clement, Giles. “Tintype Portraits of a New Generation of Folk Singers.” Vanity Fair. July 25, 2015. Accessed April 4, 2016. http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/photos/2015/07/newport-folk-festival-tintype-portraits.

Coffer, John A. “News and Information from Camp Tintype.” 2016. Accessed April 4, 2016. http://www.johncoffer.com/.

Courtney, Kent. “Press Kit for Rob Gibson Photographic Gallery.” 2016. Accessed April 4, 2016. http://kentcourtney.wix.com/gibsonphotogallery.

Ferguson, Ernest B. “Alexander Gardner Saw Himself as an Artist, Crafting the Image of War in All Its Brutality.” Smithsonian Magazine. October 8, 2015. Accessed April 4, 2016. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/alexander-gardner-saw-himself-artist-crafting-image-war-all-its-brutality-180956852/?no-ist.

Franzén, Fredrik. “Victoria Will Shoots Tintype Portraits of the Stars at Sundance.” Profoto Blog. April 7, 2015. Accessed April 4, 2016. http://profoto.com/blog/videos/victoria-will-tintype-portraits-sundance/.

Gammage, Jeff. “The Small, Stylish Comeback of the Steampunk of Photography.” Philly.com. December 22, 2015. Accessed April 4, 2016. http://articles.philly.com/2015-12-22/news/69215671_1_tintypes-fishtown-metal.

Lavédrine, Bertrand. Translated by John McElhone. Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2009.

Smithsonian Institute. “Making a Photograph During the Brady Era.” n.d. Accessed April 4, 2016.

http://www.npg.si.edu/exh/brady/animate/photitle.html.

Kerry Erlanger

Kerry Erlanger is a writer and amateur historian whose main goal is to live in a very old house. She can be found on Twitter @hellokerry, live tweeting an embarrassing amount of television shows.