Civil War Veterans and Opiate Addiction in the Gilded Age

In November 2015, two Princeton economists, Dr. Angus Deaton and Dr. Anne Case, published a startling report, which indicated that the mortality rates of poorly educated middle-aged white Americans had skyrocketed. These mortality rates, Deaton and Case argued, were not being driven by the usual suspects of diabetes or heart disease, but by suicide, alcoholism and opioid addiction. Among 45 to 54 year olds, with no more than a high school education, death rates increased by 134 per 100,000 from 1999 to 2014. This sad revelation has been billed as unparalleled in American history, with Dr. Deaton himself unable to find a historical comparison.[1]

However, rampant opioid addiction rates do have a historical parallel: here in the United States, and especially the American South, after the Civil War. Southern whites during the Gilded Age arguably had the highest addiction rates in the country, and possibly the world. How do we know? Some of the evidence is anecdotal. For instance, in the Opium Habit, published in 1868, Horace B. Day estimated that 80,000 to 100,000 Americans were addicted to opium.[2] Some of the evidence is more empirical. In 1915, Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Act, which required anyone who imported, produced, sold or dispensed narcotics to register, pay a tax and keep detailed records. David Courtwright, a historian of addiction, analyzed these records from the Harrison Act and demonstrated that addiction rates in the South were much worse than anywhere else. In Atlanta, for instance, 2 out of every 1,000 people were addicted to an opioid. The worst southern city, though, was Shreveport, Louisiana, where almost 10 out of every 1,000 were addicted to opium or morphine. These numbers were much higher than anywhere else in the United States, arguably the world.[3] Addiction rates were not born equally among Southerners either. White Southerners were far likelier to consume opium or heroin than black Southerners.

Why was opium and morphine addiction so rampant in the United States in the Gilded Age? The answer rests with the outcome of the Civil War. Thousands of Civil War soldiers who were wounded during combat, or more commonly, became sick in camp, were first dosed with opium or morphine in field hospitals during the war. Many came home struggling with addiction to narcotics, first tasted in a hospital. One Union soldier who had endured “ten months of prison life” at Andersonville, returned home with an opium addiction, first doled out at a hospital in Wilmington. He regularly consumed opium, but when he tried to quit cold turkey, found that opium had an incredibly strong hold on him. “No tongue or pen will ever describe…the depths of horror in which my life was plunged at this time; the days of humiliation and anguish, nights of terror and agony, through which I dragged my wretched being,” he wrote.[4]

Confederate soldiers returned to a defeated and humiliated South, with cities like Atlanta in near ruin. Furthermore, one out of every five southern males of military age were killed in the war. Many heartbroken families turned to drugs to cope with the devastating loss of a husband, son, brother or father. “Maimed and shattered survivors from a hundred battle-fields,” Horace B. Day wrote in 1868, “diseased and disabled soldiers released from hostile prisons, anguished and hopeless wives and mothers, made so by the slaughter of those who were dearest to them, have found, many of them, temporary relief from their sufferings in opium.”[5]

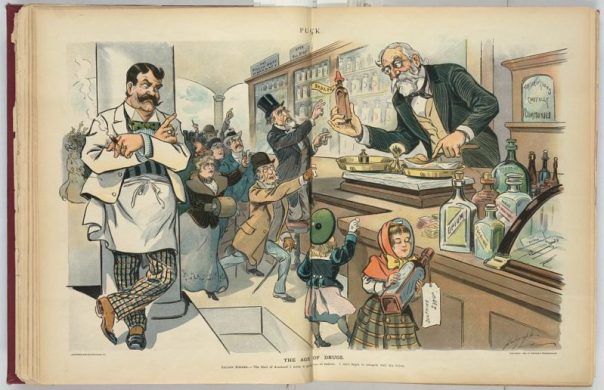

Today, much of the opioid epidemic stems from prescription drug abuse. The CDC claimed in 2014 that everyday 46 people die from a prescription drug overdose. Prescription drug abuse fueled the opioid epidemic during the Gilded Age as well. Opium, heroin and morphine were legal tools for the apothecary or physician during and after the Civil War. The science of addiction had not yet emerged, and doctors prescribed opium and morphine regularly for pain management and sleeping problems. A.M. Chappell was a veteran of the Fourteenth Virginia Infantry and had been wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg when a ball crashed through his left knee. It was a wound that Chappell noted he “would never get entirely over.”[6] By 1886, Chappell was “very poor indeed” and “with a wife and children to support.” He wrote to the Lee Camp Soldier’s Home for admission into the institution. In his letter he noted his lingering disability, poverty and his addiction to morphine. “The Dr. put me on morphine and I can’t stop that,” Chappell wrote to William R. Terry. “Can’t get it often except people give it to me.”[7]

The destruction of slavery, and the Southern slave economy, also led many Southerners to turn to drug use. The 13th Amendment to the Constitution legally overthrew the system of slavery, and four million African American men, women and children were freed. In an instant, the abolition of slavery wiped out billions of dollars in slave capital. In addition, the introduction of wage labor, along with international competition, hobbled the cotton economy. Slavery was an immoral and incredibly cruel institution with no redeeming qualities–its destruction was long overdue. But the institution’s demise wiped out vast sums of wealth in the American South, leaving many white Southerners destitute and impoverished. To cope with this sudden loss, many southerners turned to drug use. This was clear to many Americans living in the Gilded Age. “Since the close of the war,” remarked a New York opium dealer, “men once wealthy, but impoverished by the rebellion, have taken to eating and drinking opium to drown their sorrows.”[8] It also explains why the weight of addiction was not carried equally between the races. Black southerners were far less likely to be addicts, partly because the defeat of the Confederacy was celebrated not mourned.

In the wake of the death and destruction of the war, those most affected by it—soldiers and southern whites—turned to opium in alarming numbers. Many addicts were first introduced to an opioid in a hospital or by a family physician. They used opium or morphine to cope with lingering illness or injury, grief, or economic loss from the war. While much different, the modern opioid epidemic is not the first. Deindustrialization and the shredding of the social safety net has left high school educated, middle-aged whites with few options. Many have turned to opioids to cope.

[1] “Death Rates Rising for Middle Aged White Americans, Study Finds,” New York Times, November 2, 2015.

[2] Horace B. Day, The Opium Habit (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1868), 6-7.

[3] David T. Courtwright, “The Hidden Epidemic: Opiate Addiction and Cocaine Use in the South, 1860-1920” The Journal of Southern History 49, no. 1 (February 1983): 58.

[4] Anon, Opium Eating: An Autobiographical Sketch by An Habituate (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1876), 67.

[5] David T. Courtwright, “Opiate Addiction as a Consequence of the Civil War” Civil War History 24, no. 2 (June 1978): 103; Horace B. Day, The Opium Habit (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1868), 6-7.

[6] A.M. Chappell to William R. Terry, 24 May 1886, Lee Camp Soldier’s Home Correspondence, 1885-1894, Box 166, Brock Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Opium and its Consumers,” New York Tribune, July 10, 1877.

Dillon Carroll

Dillon Carroll graduated with his doctoral degree from the University of Georgia in August 2016, where he had worked with Stephen Berry, John Inscoe and Stephen Mihm. He now lives in New York City and teaches at Hofstra University and the University of Bridgeport. He spends his time revising his dissertation into a book, reading, and finding the best happy hours in the city.

7 Replies to “Civil War Veterans and Opiate Addiction in the Gilded Age”

As a Boomer, having lived through the 60s and 70s (1960s and 70s, that is . . .) I am always so surprised and disappointed that so many younger people still look to addictive drugs for answers to anything except recreation, and there is little that is “fun” about serious narcotics. Yeah, cocaine can be a group activity, but not if consumed to the extent that one os comatose. But really? Life is so tough that becoming an addiction statistic is a viable option? So sad, so sad.

Meg, you’re right, it is sad, but this isn’t a “younger person” problem, and not necessarily a recreation problem. 17 percent of older adults in the United States misuse alcohol and prescription drugs, as opposed to 10 percent of the general population, and much of that is for pain problems, not a way to quell boredom. 46 people will die today, and every day this year, due to overdose from properly prescribed medications. The problem is far bigger than bored youth.

Thanks for the concise explanation Joshua. It’s sad, but we must face the truth of this ongoing problem in this country if we are ever to resolve it.

Great article.

As a soldier, this is a serious issue. Many doctors will just give us pills for pain like that helps us. Other times we do not get the proper treatment. I’ve been doing research on veterans in regards to addiction, mental health and suicide when I came across a really good article.

Should anyone else be interested to see how this would help others here’s the page I looked at https://oceanbreezerecovery.org/blog/veteran-addiction-part-1/

I truly hope this can assist another soldier/veteran.

Altering ones mind is a natural human desire. Pursuit of this is likely second only to that of food. Every culture on Earth has for thousands if not hundreds of thousands of years vigorously pursued countless ways of altering thier consciousness. Now at least in the U.S. this ancient pursuit is illegal. Filling our prisons to numbers unknown in the rest of the world. 98 prrcent of all prisoners in the U.S. are there for drug related crimes. When the overwhelming majority of prisoners are in prison for breaking the same law I would suspect any rational individual to conclude there is something wrong with the law.

Nice Post !

Do read this article too on Level Up Opiate Rehabilitation :: https://welevelupnj.com/addiction/opiate-addiction-treatment/