Politics of the English Language: Views from 1850

As a practical tool and a badge of belonging, language is central to our sense of self. The United States has no official language, but the status of its dominant tongue shapes many contemporary conflicts over immigration and national identity. In the name of unity and assimilation, supporters of the English-only movement seek federal legislation to make English the national language and end bilingual education. Many of their opponents, in contrast, support an “English Plus” approach which would facilitate English language training while rejecting its enshrinement as the sole national language. Some argue that the English-only position cannot be divorced from nativism and racism, pointing to historical cases like Indian boarding schools, in which linguistic nationalism was entwined with white supremacy.

This discussion will not end soon; nor are many of its elements particularly new. In 1850, U.S. senators held a brief but fascinating debate over language which revealed intriguing patterns in partisanship, regionalism, and notions of belonging. Their arguments reveal that language has always been controversial in a nation seeking to balance “pluribus” and “unum.”

President Millard Fillmore unwittingly triggered the debate when he sent his annual message to Congress in December 1850. Today, the State of the Union Address is a media event, delivered in person and broadcast live. In 1850, Fillmore followed then-standard protocol and simply wrote the message for clerks to read to Congress. Later, it was distributed nationwide through pamphlets and newspapers.

Fillmore presided over a rapidly-changing country. Massive immigration from Germany and Ireland, mostly into the North, had swelled the foreign-born population to 9.7% of the total by 1850.[1] Backlash came swiftly, as nativists assailed the newcomers, especially Irish Catholics, as cultural, political, and economic threats.

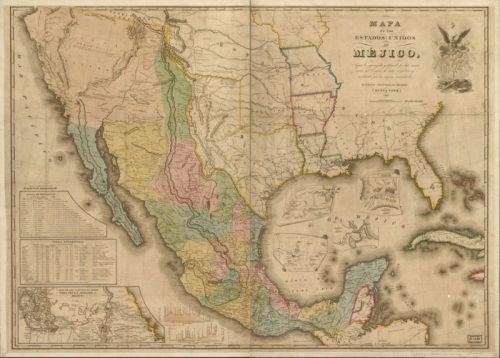

Meanwhile, the U.S.-Mexican War had redrawn the country’s borders and expanded its citizenry. According to the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848), Mexico ceded California and most of the modern-day Southwest – some 500,000 square miles – to the United States. The treaty also brought tens of thousands of Mexican citizens under the U.S. flag; they had one year to decide whether to remain, and accept U.S. citizenship, or depart for Mexico. Most, including around ten thousand people in California, opted to stay. After a fierce congressional struggle, California gained statehood as part of the Compromise of 1850. That December, two California senators – William M. Gwin and John C. Frémont – took their seats in Washington.[2]

On December 12, Gwin proposed that the Senate commission and print two thousand copies of a Spanish translation of Fillmore’s message.[3] Undoubtedly, he wanted to send the translated document back to his constituents, particularly Spanish-speaking Californios, some of whom owned vast sheep and cattle ranches and participated actively in politics.

Five days later, the Senate debated Gwin’s proposal. Gwin opened with an ingenious argument: aware of the rising nativist tide, he asserted that immigrants from abroad “ought to be prepared to read these documents” in English. But this case, Gwin contended, was different because Spanish speakers in California and New Mexico were not immigrants; they had simply remained in their homes, and translating the annual message would have “a favorable effect” upon them. Gwin tried to deflect the discussion away from the contentious issue of immigration and onto a question of fairness toward his unique constituents.[4]

The subsequent debate covered rather familiar ground. George E. Badger of North Carolina agreed that this case was exceptional. The Californios had been made American citizens “almost against their consent,” and while he hoped they would learn English, complete assimilation would take time. Since they had no access to Spanish-language sources of information about U.S. politics, providing the translation would hasten, not delay, cultural and political adjustment. Henry S. Foote of Mississippi expressed mortification that anyone would object to Gwin’s plan, since it would educate Spanish speakers in American citizenship.[5]

Opponents were unconvinced. Augustus C. Dodge, an Iowan, reversed Gwin’s argument and proclaimed that he would rather translate the message for immigrants who deliberately chose to relocate, than for a conquered people. Other critics noted that nothing comparable had been done when the U.S. acquired Louisiana or Florida, areas with significant French- and Spanish-speaking populations. William L. Dayton (New Jersey) and James W. Bradbury (Maine) raised a classic slippery-slope objection, warning that the Senate would be asked to print in every language spoken nationwide. Isaac P. Walker (Wisconsin) proposed amending the resolution to print translations in German and Norwegian; his purpose, he readily admitted, was to torpedo Gwin’s efforts. Wisconsin’s 90,000 Germans and Norwegians, he insisted, spoke no English but did not request translations. Foote retorted that Gwin’s constituents wanted the translation because they lacked newspapers which could print public documents in their native tongue, whereas Germans could read Fillmore’s message in the thriving German-language press.[6]

Gwin’s proposal ultimately failed when the Senate voted 27-16 in favor of Bradbury’s motion to table the resolution; thus, an ‘aye’ vote signaled opposition to providing a Spanish translation. Broken down by party and region, the vote reveals trends not visible in the brief debate and reveals how partisan and ideological concerns shaped senators’ decisions.[7]

Both major parties were split, with Democrats more likely to oppose Gwin’s resolution than Whigs: 68% of Democrats voted to table, compared with 59% of Whigs. The lone Free Soil senator, Salmon Chase of Ohio, voted against tabling.

Northerners and southerners were similarly divided over Gwin’s proposal, with southerners (68% voted to table) somewhat more inclined to oppose the translation than northerners (58% voted to table). When broken into eastern (east of Ohio and Alabama) and western subregions, the geographic distinction is clearer: southwestern and northeastern senators were strongly against Gwin’s proposal, with 75% of each group voting to table, while southeasterners were somewhat less opposed (57% for tabling) and northwesterners were actually in favor of the translation (only 42% supported tabling).

Combining regional and party affiliations exposes interesting patterns: Northeastern and southeastern Democrats unanimously opposed translation, perhaps because they saw it as a bid to spread the message of a Whig president in the far West, and because they faced a rising wave of nativism back home, particularly in northeastern cities. Thus, they had several motives to oppose Gwin. Southwestern Democrats were next most likely to support tabling, followed by northeastern Whigs. For the former, opposition was probably driven by partisanship, while for the latter, regional rivalries and nativist sentiments were probably paramount.

Northwestern Democrats were evenly split. Most were critical of nativism and courted immigrant voters, although partisanship may have dampened their enthusiasm for translating a Whiggish speech. Interestingly, the only two states whose senators united in favor of Gwin’s measure were in the northwest: Ohio and Illinois.

Most southeastern Whigs opposed tabling Gwin’s resolution; under less nativist pressure than their northeastern counterparts, they had less reason to oppose spreading the Whig message by translating Fillmore’s words. Finally, northwestern Whigs (and the only Free Soiler, a northwesterner) unanimously opposed tabling the resolution. With partisan incentives to support translation and less nativist pressure upon them than their northeastern colleagues, northwestern Whigs emerged as Gwin’s staunchest allies. Since Gwin was a southern-born Democrat, the vote reminds us that politics always make strange bedfellows.

Gwin’s resolution has been overshadowed by the Compromise of 1850 which preceded it and the ethnic and sectional strife which followed throughout the 1850s. But the debate and vote on Gwin’s proposal demonstrate the complexity of conflicts over language and belonging. Amid an era of mounting sectionalism, other influences, including partisanship, nativism, and nationalism, clearly shaped the discussion and vote prompted by Gwin’s proposal. In unsettled political times, success clearly depends on building coalitions, no matter how unlikely they may seem.

[1] Paul Schor, Counting Americans: How the US Census Classified the Nation, trans. Lys Ann Weiss (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 140.

[2] Richard Griswold del Castillo, The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), 62-86; William Henry Ellison, A Self-Governing Dominion: California, 1849-1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1950), 78-101.

[3] Congressional Globe, 31 Cong., 2 Sess., 35 (December 12, 1850).

[4] Ibid., 66 (December 17, 1850).

[5] Ibid., 66-67 (December 17, 1850).

[6] Ibid., 66-68 (December 17, 1850).

[7] The votes that are discussed in the following paragraphs are listed on ibid., 69 (December 17, 1850).

Michael E. Woods

Michael E. Woods is Associate Professor of History at University of Tennessee-Knoxville. He is the author of Bleeding Kansas: Slavery, Sectionalism, and Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border (Routledge, 2016) and Emotional and Sectional Conflict in the Antebellum United States (Cambridge, 2014), which received the 2015 James A. Rawley Award from the Southern Historical Association. His most recent book is entitled Arguing until Doomsday: Stephen Douglas, Jefferson Davis, and the Struggle for American Democracy (North Carolina, 2020).