UVA Unionists: A Digital Project Studying University of Virginia Alumni Who Stayed Loyal to the Union

Note: “UVA Unionists” is one of two digital projects at the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History that shed light on the area’s untold Unionist stories. The other project, “Black Virginians in Blue” [link to Will Kurtz’s Muster blog post], launched in April. See Will Kurtz’s recent Muster post on this project.

In October 1913, the Staunton Daily News called attention to a “grave oversight on the part of our Virginian schools and colleges.” The University of Virginia and other institutions had kept careful records of their Confederate alumni and celebrated them with reunions, banquets, and monuments. But they had “almost entirely overlooked their sons who were in the Federal forces.” The writer praised these “neglected alumni,” insisting that their wartime achievements—if properly recognized—would bring honor and fame to Virginia’s colleges. As Virginians “rejoice in a re-united land,” he observed, they could “surely remember with pride their sons who saw the path of duty differently.” Later that month, UVA’s Alumni News reprinted the article and confessed that “no complete list has been made of the University alumni who saw service in the Union army.”[1]

Now, more than a century later, the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History has answered that call. We transcribed antebellum student catalogues and systematically searched databases on Ancestry.com, Fold3.com, and Newspapers.com. We examined pension and service records at the National Archives and manuscript collections across the country. After four years of research, we have identified 68 UVA students, alumni, and faculty members who served in the Union military. We have also found dozens more who supported the Union cause as civilians, including Congressman Henry Winter Davis and Maryland Governor Thomas Swann. Our “UVA Unionist” project, which officially launches on May 4, tells these men’s stories.

In April 1861, these UVA Unionists ranged in age from 14 to 57, with a median age of 26.5. The Staunton Daily News editor assumed they “must have been northern boys…who stuck to their people and their native land.” In reality, two-thirds were born in the South: in Kentucky, Maryland, Virginia, Mississippi, Texas, and South Carolina. Nearly half came from slaveholding households, and several belonged to prominent political families. Stephen Kennedy and Charles Ewing were the sons of United States Senators, and army surgeon John Fox Hammond was the brother of South Carolina Governor James Henry Hammond.[2]

Before the war, most UVA Unionists were doctors, lawyers, farmers, teachers, or students. Forty-eight (71 percent) served as officers during the war, and seven ultimately became generals. Only about thirty, however, served on the front lines. The others spent the war as prison guards, paymasters, recruiters, medical personnel, or home guards. Two UVA Unionists died during the war: James Gilliss, superintendent at the Naval Observatory, died of a stroke in February 1865, and his colleague Alexander Pendleton died of an unknown disease later that month. Many others, however, suffered from illness or injury, and at least six became prisoners of war. Most served the Union cause faithfully, and only one man deserted from the army.[3]

After the war, as UVA’s faculty and alumni embraced the Lost Cause, they largely erased these men from the university’s history. The Alumni Bulletin valorized UVA’s Confederate veterans, and an 1878 catalogue noted the Confederate service of more than 2,000 alumni. UVA hosted a Confederate reunion in 1912, and President Edwin Alderman asked alumni to donate their wartime relics—“anything Confederate”—to the university. These publications, however, mentioned only a small handful of UVA Unionists, and the university’s ceremonies and monuments excluded them entirely. One alumnus insisted “there was no Union feeling in the state,” and another agreed that secession brought “all, almost without exception, to the same mind.”[4]

To be sure, the overwhelming majority of UVA alumni supported secession and sided with the Confederacy. Our research suggests that half of all antebellum alumni served in the Confederate military, including 89 percent of the men who attended UVA in 1860-61. Only about 1 percent of UVA’s students, alumni, and faculty served in the Union military. Our project does not attempt to equate these figures. It does, however, shed light on the deep divisions within the nineteenth-century South. Roughly 300,000 White southerners and 150,000 former slaves served in the Union military, and UVA’s Unionists are part of this larger story.[5]

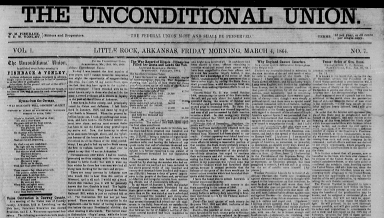

Most were political moderates who fought not to abolish slavery but rather to preserve the Union. Eight men were already serving in the United States military when the war began, and ten more enlisted by May 1861. As James Winslow, a Unionist who attended UVA in 1861, explained, loyal Americans would “maintain the integrity of the Union…if it cost every drop of blood & every dollar in the country.” New York merchant Robert Shannon agreed, recruiting men to “sustain the government” and fight the “holiest war in which patriots ever engaged.” Arkansas editor William Fishback declared the Union the “best government on earth”—a beacon of hope in a world ruled by despotism and heresy.[6]

Despite their moderation, many UVA Unionists ultimately accepted emancipation as a military necessity. Missouri lawyer James Overton Broadhead, for example, began the war as a proslavery Unionist. He served in Missouri’s 1861 constitutional convention, where he forcefully defended both slavery and Union. During the war, however, his convictions slowly evolved. In 1862, as U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri, he upheld the First Confiscation Act and instructed army officials to liberate Confederate owners’ slaves. The following year, he urged Missourians to adopt gradual emancipation. Although the plan would keep many African Americans in apprenticeships for decades, Broadhead explained, it would establish the “great leading distinction between slavery and freedom…the negro would no longer be a thing, but a person.”[7]

After the war, most UVA Unionists hoped to quickly reunite the country, and they largely opposed the “radicalism” of Reconstruction. Broadhead, for instance, severed ties with Republicans and became a leader in Missouri’s Conservative Party. He argued that Congressional Reconstruction “deprived our people of both religious and civil liberty” and denied them a “republican form of government.” He denounced Republicans’ experiment in biracial democracy and championed reconciliation with former Confederates. The country, he claimed, “needs repose and order,” and he could “never justify the acts of reconstruction, or the plunder of the Southern people.”[8]

A handful of UVA Unionists, however, became champions of freedom. Robert Shannon served as a federal commissioner in Louisiana, where he vigorously enforced the Civil Rights Act of 1866. He imprisoned White Louisianians for terrorizing former slaves, arrested election officials for keeping freedmen from voting, and arraigned state judges for failing to defend African Americans’ rights. Oregon editor Benjamin Franklin Dowell defended African-American suffrage and civil rights, insisting the right to vote made former slaves “not only free in name but in fact.” Most famously, Maryland Congressman Henry Winter Davis became an architect of Congressional Reconstruction. He co-authored the Wade-Davis Bill, helped pass the Thirteenth Amendment, and fought for legal and political equality for all men.[9]

Despite their small numbers, these UVA Unionists remind us of the ideological power of the Union, which enshrined political liberty and economic opportunity for all White men. Benjamin Dowell, for instance, championed the “republican principles” of self-government and vowed to live under “the stars and stripes, as long as life shall last.” These men’s stories remind us of the conservatism of most loyal Americans and help explain the failures of Reconstruction. But they also speak to the Civil War’s contested and transformative potential and reveal the ways that southern intransigence both hardened northern resolve and embedded the ideals of biracial democracy in the Constitution. Their devotion to the Union belies the Lost Cause myth of southern unity and reveals the deep and enduring divisions in the nineteenth-century South.[10]

[1] The Staunton Daily News, 14 October 1913; University of Virginia Alumni News 2, no. 4 (29 October 1913), 37.

[2] The Staunton Daily News, 14 October 1913.

[3] See Brian Neumann, “UVA Unionists: The University of Virginia’s ‘Neglected Alumni,’” Magazine of Albemarle Charlottesville History 78 (2020), 73-108.

[4] Albert T. Bledsoe, Is Davis a Traitor, or Was Secession a Constitutional Right (Baltimore: Innes & Company, 1866), v; James M. Garnett, “Personal Recollections of the University of Virginia at the Outbreak of the War of 1861-65,” Alumni Bulletin of the University of Virginia, 3rd ser., vol. 5, no. 3 (July 1912), 338; William W. Old, “The Student Volunteers of 1861,” Alumni Bulletin of the University of Virginia, n.s., vol. 5, no. 5 (March 1906), 292-295; Students of the University of Virginia: A Semi-Centennial Catalogue with Brief Biographical Sketches (Baltimore: Charles Harvey, 1878).

[5] William W. Freehling, The South vs. The South: How Anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the Course of the Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), xiii.

[6] James A. Winslow to John B. Minor, 21 May 1861, Papers of John B. Minor, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia; New York Daily Herald, 21 May 1861; Unconditional Union (Little Rock, AR), 23 January 1864.

[7] Fremont (OH) Weekly Journal, 19 October 1860; Journal of the Missouri State Convention Held at Jefferson City and St. Louis, March 1861 (St. Louis, MO: George Knapp, 1861), 114-233; James O. Broadhead to Bernard G. Farrar, 2 February 1862, in Ira Berlin et al., eds., The Destruction of Slavery, 1st ser., vol. 1, Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 425-426; Journal of the Missouri State Convention Held in Jefferson City, June 1863 (St. Louis, MO: George Knapp, 1863), 297.

[8] Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), 22 August 1866; Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, WI), 24 September 1874; St. Louis (MO) Post-Dispatch, 26 September 1882.

[9] The Daily True Delta (New Orleans, LA), 11 February 1864; The New Orleans (LA) Republican, 5 January 1868, 3 May 1868, and 6 June 1868; The Natchez (MS) Democrat, 25 July 1868; The Oregon Sentinel (Jacksonville, OR), 5 December 1868; Bernard C. Steiner, Life of Henry Winter Davis (Baltimore, MD: John Murphy, 1916); Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis: Antebellum and Civil War Congressman from Maryland (New York: Twayne, 1973).

[10] Weekly Oregon Statesman (Salem, OR), 28 April 1862; The Oregon Sentinel (Jacksonville, OR), 26 November 1864.

Brian Neumann

Brian Neumann received his PhD from the University of Virginia and serves as editorial assistant for the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History. He is the author of Bloody Flag of Anarchy: Unionism in South Carolina during the Nullification Crisis (forthcoming from LSU Press) and “UVA Unionists: The University of Virginia’s ‘Neglected Alumni,’” Magazine of Albemarle Charlottesville History 78 (Albemarle County Historical Society, 2020).

One Reply to “UVA Unionists: A Digital Project Studying University of Virginia Alumni Who Stayed Loyal to the Union”