From Gray to Blue: An Odyssey of Deserting the Confederate Army and Joining the U.S. Army

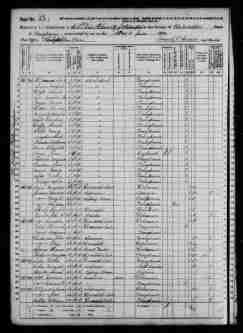

Though radical at first, the U.S. Army’s recruitment of Confederate prisoners of war and deserters was not unreasonable by the winter of 1863-1864. “Thousands of Union soldiers were nearing the end of their three-year voluntary enlistment and draft calls were causing riots in Northern cities.”[1] Combined with prolonged indecision from Lincoln’s War Department, several Federal prison commanders became emboldened to tacitly enlist witting ex-Confederates into Federal regiments. Indeed, each of these southerners had their motivation(s) to serve their former enemy: desperation from imprisonment, disillusionment with the Confederacy’s cause, or a determination to survive by any means. Among these pioneering “Galvanized Yankees” were brothers Samuel Kael Groah and Andrew Jackson Groah.

On April 18, 1861, one day after Virginia voted to secede from the United States, the two Shenandoah Valley natives answered the call to arms. Along with approximately 2,600 fellow militiamen, the brothers quickly assembled at the Harpers Ferry Armory to arm and prepare for the anticipated civil war. On May 19, 1861, the Groah brothers mustered into the Fifth Virginia Infantry Regiment of the First Brigade Virginia Volunteers, commanded by Brigadier General Thomas Jackson. On July 2, 1861, the Groah brothers received their baptism by fire at the Battle of Hoke’s Run. During the First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas, the First Brigade and its commander earned their reputable sobriquet “Stonewall.”[2]

Over early 1862, fortunes changed as these rebels weathered the ill-fated Romney Expedition, retreated in defeat at the First Battle of Kernstown, and camped at Rude’s Hill nearby New Market, Virginia. As troops neared the end of their one-year service term, the Confederate Congress authorized bounties and furloughs to encourage reenlistments. For reasons unknown, Samuel and Andrew “deserted from the company at Camp Rude’s Hill, April 6, 1862. Refused to reenlist.”[3] Incidentally, just ten days later, the Confederacy mandated three years of service for new recruits and an additional two for those serving since 1861.[4]

Despite its grandeur, the Stonewall Brigade suffered a staggering desertion rate. The Fifth Virginia alone reported 315 desertions throughout 1862-1863.[5] Unlike other Confederate troops serving far from their homes, Virginians could escape to their homesteads, but not without risks. “Patrols were actively searching every possible hiding place of those recreant.”[6] In August 1863, the Confederacy offered a pardon to known deserters and those accused of absence without leave, hoping clemency could entice their return within twenty-days.[7] The matter also proved challenging for Federal commanders. One Major General reported Confederate deserters concealed in wooded hills “who preferred to live as outlaws rather than risk the chance of being returned to the rebel army.”[8]

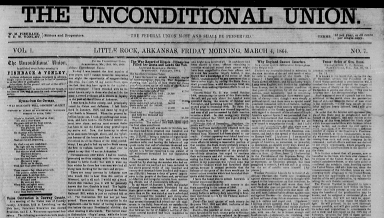

On September 7, 1863, seventeen months since their desertion, Samuel and Andrew were arrested near Beverly, West Virginia by order of Union Brigadier General William Averell.[9] Presumably, the brothers fled the Shenandoah Valley, traversed the Allegheny Mountains, and took refuge in Unionist territory until Averell’s search-and-destroy raids prompted their discovery. Samuel and Andrew were next transported by rail to Wheeling, West Virginia and jailed in the Athenaeum, a warehouse/theater-turned transitory prison depot for captured Confederates, suspected spies, civilians who refused the oath of allegiance, dissenting local journalists, and court-martialed Union soldiers. Lacking ventilation, confined to small cells or shared spaces, and often with a ball and chain affixed to their legs, some inmates unsurprisingly dubbed the Athenaeum “Lincoln’s Bastille.”[10] Samuel and Andrew’s imprisonment was brief. On September 19, 1863, they were released by order of Union Brigadier General Benjamin Kelly, commander of the Department of West Virginia.[11] In October 1863, their cases underwent disposition in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

Rather than be sent to a prisoner of war camp, the Groahs opted to serve the United States. Such desires were not uncommon among Confederates detained in the North. As one Federal prison commander noted, “many of them have been conscripted in the rebel service and are now anxious to be avenged for the wrongs done them…Others were induced to enter the rebel service through misrepresentations of wicked and designing men.”[12] Ex-Confederates willing to aid the Federal war effort, the Commissary-General of Prisoners instructed, “may be permitted to do so when the examining officer is satisfied of the applicant’s good faith and that the facts of his case are as he represents them.”[13] Perhaps, the Groahs shared their paternal lineage to Pennsylvania as well as recounted the allure of secession in 1861, best summarized by one Union officer: “they eagerly embraced a cause promising to disrupt the established commercial and social status of the country, having in any change hope of possible advantage and fear of nothing worse than their present position.”[14] Such plausible factors were sufficient to enroll the brothers into the U.S. Army.

Andrew enlisted November 30, 1863 in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania and mustered into the Third Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery Regiment.[15] Andrew’s service with the Third Pennsylvania, then a coastal defense battery, was limited to Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. On March 17, 1865, he was reassigned to the Fourth U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of six units comprised of rebel prisoners-turned Federal soldiers.[16] Uneasy of sending them to the frontlines, the U.S. Army’s high command dispatched these “Galvanized Yankees” to the Great Plains. Among other tasks, these soldiers manned frontier outposts, guarded supply wagons, and, on occasion, quelled Native American uprisings. The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 and the Sand Creek massacre of 1864, in particular, epitomized this struggle for expansion on the American frontier.[17] In June 1865, Andrew arrived at Fort Sully, located on the east bank of the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota, for the monotonous assignment of garrison duty at a truly desolate location. “There was no grass or wood within two miles.”[18] Andrew remained at Fort Sully until his regiment moved to Sioux City, Iowa in September 1865. There, on November 27, 1865, Andrew was discharged.[19]

Samuel enlisted January 7, 1864 in Jefferson County, Pennsylvania and mustered into the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment.[20] Unlike his younger brother, Samuel fought against his former Confederate brethren. Between May-August 1864, the 148th Pennsylvania saw action at the Wilderness, Po River, Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna, Totopotomoy, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Deep Bottom, Strawberry Plains, and Ream’s Station.[21] In September 1864, Samuel was detailed to his division’s headquarters where he served until the Confederacy’s surrender. Briefly assigned to the Fifty-Third Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment after the war, Samuel was discharged on June 30, 1865 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.[22]

Perhaps, the most notable of Samuel’s service transpired during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. On May 10, 1864, he was wounded in action near the Po River.[23] There, a forested section near the Federal line became engulfed in a blazing inferno, presumably sparked from Confederate artillery. Samuel and his fellow soldiers, were, quite literally, forged in fire. Despite his injury, Samuel remained in the ranks. Two days later, the 148th Pennsylvania stormed the “Mule Shoe” salient, whose entrenched rebel defenders included the Fifth Virginia – Samuel’s prior Confederate unit. “Within thirty minutes, the Stonewall Division virtually ceased to exist as a command.”[24] How poetic that among the Federal soldiers who contributed to the demise of one of the Confederacy’s most revered units was a former Confederate from its very ranks. Truly, an emblematic scene of the Civil War.

Perhaps, the most enduring element of the Groah’s journey is rooted in their unshakeable brotherhood bond. Though Virginia was their home, and, by extension, the Confederacy their cause, these brothers also recognized the importance of family and survival. Indeed, some may shame them as Southern Unionists, turncoat opportunists, or scalawags. Yet, as the United States approaches the 160th anniversary since the commencement of the American Civil War, Samuel and Andrew also embody the torn loyalties and complexities of the nation’s most cataclysmic conflict.

[1] Dee Brown, The Galvanized Yankees (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1963), 3.

[2] “Confederate Soldiers from the State of Virginia – Groah, Samuel K – Fifth Infantry,” Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia, Record Group 109, Microfilm 324, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://catalog.archives.gov/id/96414285, Accessed April 14, 2021; “Confederate Soldiers from the State of Virginia – Groah, Andrew J – Fifth Infantry,” Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia, Record Group 109, Microfilm 324, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://catalog.archives.gov/id/96414274, Accessed April 11, 2021.

[3] Ibid.

[4] James Martin, “Civil War Conscription Laws.” In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress, Washington, D.C., November 15, 2012, https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2012/11/civil-war-conscription-laws/.

[5] Lee A. Wallace, Jr., 5th Virginia Infantry, 1st Edition, (Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1988), 77.

[6] Sanford Cobb Kellogg, The Shenandoah Valley and Virginia, 1861 to 1865: A War Study, (New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1903), 125.

[7] U.S. Department of War, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 30, Part 4, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1890), 489.

[8] U.S. Department of War, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 2, Volume 6, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899), 207. Author’s Note: “Returned” is a reference to prisoner of war exchanges between the Union and Confederate armies throughout the early portion of the Civil War.

[9] “Confederate Soldiers from the State of Virginia,” National Archives.

[10] Edward L. Phillips, “Wheeling’s Athenaeum 1854-1868,” West Virginia Historical Society Quarterly 17, no. 2 (April 2003), http://www.wvculture.org/history/wvhs/wvhs1722.html.

[11] “Confederate Soldiers from the State of Virginia,” National Archives.

[12] The War of the Rebellion, Series 2, Volume 6, 820.

[13] Ibid., 186.

[14] Ibid., 197.

[15] “4th US Volunteers, Go-J,” Compiled Service Records of Former Confederate Soldiers who Served in the 1st Through 6th U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiments, 1864-1866, Record Group 94, Microfilm 1017, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed through Fold3, https://www.fold3.com/image/119078638, Accessed April 11, 2021. Author’s Note: The Groah surname is interchangeably written as “Grovah” on Andrew’s Union Army paperwork.

[16] “4th US Volunteers,” National Archives.

[17] Stephen Kantrowitz, “Jurisdiction, Civilization, and the Ends of Native American Citizenship: The View from 1866,” Western Historical Quarterly 52 (Summer 2021): 194.

[18] “Old Fort Sully.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/pierre_fortpierre/old_fort_sully_pierre.html. Accessed April 21, 2021.

[19] “4th US Volunteers,” National Archives.

[20] “Compiled Military Service Record of Private Samuel K. Groh, Company I, 148th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment.” Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Volunteer Organizations During the American Civil War, Record Group 94, Microfilm 398, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://catalog.archives.gov/id/66390638. Accessed April 11, 2021. Author’s Note: The Groah surname is interchangeably written as “Groh” on Samuel’s Union Army paperwork.

[21] Kate M. Scott, ed. History of Jefferson County, Pennsylvania, (Syracuse: D. Mason & Co., Publishers, 1888), 180.

[22] “Compiled Military Service Record of Private Samuel K. Groh,” National Archives.

[23] Joseph Wendel Muffly, et al., The Story of Our Regiment: A History of the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteers, (Des Moines: Kenyon Printing & Mfg Co., 1904), 1054.

[24] Jeffrey D. Wert, A Brotherhood of Valor: The Common Soldiers of the Stonewall Brigade, C.S.A. and the Iron Brigade, U.S.A., (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 300.

Kyle Nappi

Kyle Nappi is a descendant of the brothers Samuel Kael Groah and Andrew Jackson Groah and the great-great-great-grandnephew of William Welsh. An alumnus of The Ohio State University, Kyle serves as a national security policy specialist in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. He is also an independent researcher and writer of military history (chiefly the World Wars), having interviewed ~4,500 elder military combatants across nearly two-dozen countries. Kyle would like to acknowledge the archival assistance of Grand Valley State University's Leigh Rupinski and Tracy Cook.

The Tom Watson Book Award honors the finest book on the “causes, conduct, and effects, broadly defined, of the Civil War” and is presented by the Watson-Brown Foundation and the Society of Civil War Historians. In 2020, the award went to Thomas J. Brown for his excellent study Civil War Monuments and the Militarization of America (2019). At a virtual gathering, to replace the in-person banquet at the Southern Historical Association annual meeting, Brown delivered an intriguing analysis, titled “Iconoclasm and the Monumental Presence of the Civil War.” Brown’s essay places the debates about memorialization (up to November 2020) within a longer trajectory of critique and iconoclasm. Brown adroitly analyzes works by artists and writers An-My Lê, Kehinde Wiley, Natasha Trethewey, and Krzysztof Wodiczko and concludes with a stirring examination of the community takeover of the Robert E. Lee Monument on Memorial Avenue in Richmond. The essay is a terrific example of how historians can help contextualize and clarify the terms of contemporary public debate.

The Tom Watson Book Award honors the finest book on the “causes, conduct, and effects, broadly defined, of the Civil War” and is presented by the Watson-Brown Foundation and the Society of Civil War Historians. In 2020, the award went to Thomas J. Brown for his excellent study Civil War Monuments and the Militarization of America (2019). At a virtual gathering, to replace the in-person banquet at the Southern Historical Association annual meeting, Brown delivered an intriguing analysis, titled “Iconoclasm and the Monumental Presence of the Civil War.” Brown’s essay places the debates about memorialization (up to November 2020) within a longer trajectory of critique and iconoclasm. Brown adroitly analyzes works by artists and writers An-My Lê, Kehinde Wiley, Natasha Trethewey, and Krzysztof Wodiczko and concludes with a stirring examination of the community takeover of the Robert E. Lee Monument on Memorial Avenue in Richmond. The essay is a terrific example of how historians can help contextualize and clarify the terms of contemporary public debate.

Catherine A. Jones has won the $1,000 George and Ann Richards Prize for the best article published in The Journal of the Civil War Era in 2020. The article, “The Trials of Mary Booth and the Post-Civil War Incarceration of African American Children,” appeared in the September 2020 issue.

Catherine A. Jones has won the $1,000 George and Ann Richards Prize for the best article published in The Journal of the Civil War Era in 2020. The article, “The Trials of Mary Booth and the Post-Civil War Incarceration of African American Children,” appeared in the September 2020 issue.

Thirty years before Union armies conquered the Deep South, Mexican troops found a slave society at war with itself during the “Texas Revolution.” During the spring of 1836, President Santa Anna’s army sacked San Antonio and then marched on the exposed plantation zone of eastern Texas. Hundreds of enslaved people rose up and escaped from bondage along the Brazos and Trinity Rivers during the early months of the crisis. Some of these maroons ended up fighting alongside Mexican troops, Tejano loyalists, emigrant Natives, and even Comanche bands during a series of insurgencies that lasted another decade. Although Anglo rebels secured Texas’ de facto independence from Mexico at the Battle of San Jacinto, never had plantation slavery expanded so quickly or on such a large scale into the territory of a powerful Indigenous nation. The economies of violence animating the Comancheria and the Cotton Kingdom proved incompatible. To maintain their tenuous control of Texas, paramilitary slavers (mythologized as “rangers” or “Indian fighters”) and the U.S. Army would wage brutal wars to exterminate and confine the Comanches and other Southern Plains peoples that lasted until 1875.

Thirty years before Union armies conquered the Deep South, Mexican troops found a slave society at war with itself during the “Texas Revolution.” During the spring of 1836, President Santa Anna’s army sacked San Antonio and then marched on the exposed plantation zone of eastern Texas. Hundreds of enslaved people rose up and escaped from bondage along the Brazos and Trinity Rivers during the early months of the crisis. Some of these maroons ended up fighting alongside Mexican troops, Tejano loyalists, emigrant Natives, and even Comanche bands during a series of insurgencies that lasted another decade. Although Anglo rebels secured Texas’ de facto independence from Mexico at the Battle of San Jacinto, never had plantation slavery expanded so quickly or on such a large scale into the territory of a powerful Indigenous nation. The economies of violence animating the Comancheria and the Cotton Kingdom proved incompatible. To maintain their tenuous control of Texas, paramilitary slavers (mythologized as “rangers” or “Indian fighters”) and the U.S. Army would wage brutal wars to exterminate and confine the Comanches and other Southern Plains peoples that lasted until 1875.