“A Grand Thing”: The Rebirth of Milwaukee’s Soldiers’ Home

When the U. S. government lived up to Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural promise to “care for him who shall have borne the battle,” it chose Milwaukee as one of the sites for the three original branches of the National Asylum (later Home) for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS). The first men moved into a few farm buildings on a hill west of the city in 1867; in 1869, an impressive, several-stories high structure was completed. Over the next two decades, massive wings were added to the main building and a couple of dozen other structures—including a theater, a chapel, and a library—were built. By 1900, 2,000 Civil War veterans lived there. They were mostly white—although a few African American veterans were admitted—and mostly single. Many were immigrants. And they came from all over the United States.

At about that time, Orlando Burnett, a writer for a western Wisconsin newspaper, visited Milwaukee to report on the Home. His article began with a section called “Memories Round a Bedside.” A proud staff member told him of the convenience of having a card containing the patient’s medical and personal information attached to the foot of his bed in the hospital ward. “When he dies,” he noted, “we have here all his record.” Burnett noticed that “[t]he man in the bed stirred uneasily.” The oblivious guide went on to talk about the man as though he wasn’t lying a few feet away. But Burnett could not shake the image of the old soldier. “The man on the bed must have been somebody once. . . . Women had once admired his fine-lined face and kissed it.” Now, however, it had assumed “the pallor that the angel Death paints us with when nature reports that the machinery is worn out.” Years ago the man had been “young and full of fire. He had marched from home with cheers in his ears, and he had seen the foe. He had thought great thoughts on picket duty under the stars, and he had done a man’s work in the world.” But now he was so weary that he could not close his mouth, and he cared little about what people thought when they looked at him. “He was rather a tired child—this big, old man, who once marched with Gibbon and Bragg [Generals John Gibbon and Edward Bragg, commanders of the famed Iron Brigade]. And as he lay on his pillow, the white bed clothes wrapped about the thin, gaunt frame, he brought no explanations or beseechings. He seemed to want nothing of God but a chance to sleep for ten million years.” Before going on to describe the home’s 1400-seat theater, the well-stocked library, the spotless kitchen, the anti-drinking Keeley club, and the ways in which the men who could work were occupied and the men who could not were disciplined, Burnett admitted, “It knocks a man’s theological systems into little pieces to see an old man who fought for a nation on his death bed.”[1]

The melancholy tone continued as he broadened his gaze. A fifth of the men in the home were kept in the hospital, where they were treated for old wounds and new maladies, from cancer to injuries caused by accidents to cuts and bruises suffered in fights. Although many received pensions, most were quite poor, and could probably not support themselves outside the home. “Many of them are thus saved from the poor house.” The men were largely “out of touch with home and women, who gladden life and smooth the pathway to the grave. Death and separation have done their work and the old fellows, stoical, serene, free from cares, await their end.” The administrators who showed Burnett around the Home were no doubt hoping for a cheery account of the good work being done on behalf of the old soldiers—and the article did provide a positive report. But the tone of the piece was bittersweet, at best, and deeply ambiguous.[2]

Although exaggerated—Burnett was clearly working through some of his own anxieties about aging and mortality—the condition and status of the men living in the home, particularly the poor, speechless, slack-jawed veteran of the Iron Brigade, represented in many ways the odd position of Civil War veterans in late nineteenth century Wisconsin and the United States, where they were both honored and neglected.

A century later, and sixty years after the last Civil War veteran had died, the buildings in which those veterans lived had fallen into a similar kind of dignified neglect. Like all NHDVS facilities, the Veterans Administration had taken over the Northwestern Branch in the 1930s. A few decades later, a new VA hospital was built down the hill from the old Home. The Veterans Administration repurposed some of the old buildings for offices, employee housing, storage, and other mundane purposes—the old library and bowling alley were still in use, for instance, and the regional veterans’ benefits office and the massive Wood National Cemetery were also administered from offices located in the historic complex. But most of the roughly two dozen buildings that had survived from the first two or three decades of the Home’s existence fell into a state of elegant, even romantic disrepair. Treasured by those who admired their architecture and historical importance, the structures were twice been honored by preservationists: the state of Wisconsin created the National Soldiers’ Home Historic District in 1994 and the federal government created the Milwaukee Soldiers Home National Historic Landmark District in 2011.

And yet the Home’s main landmark, the old main building that could be seen for miles around, ending up laying empty for a number of years, as forgotten, it seemed, as the old soldiers who had lived there a century before. Indeed, as I wrote in my 2017 essay for Gary Gallagher’s and Matt Gallman’s Civil War Places, “In a way, the old buildings are now stand-ins for the old soldiers,” shunted aside and forgotten. “Some of the buildings are in appalling condition, with construction fences blocking entrances, roofs sagging raggedly, and paint faded and chipped. The clumsily executed stained glass window of a mounted Gen. U. S. Grant, presented to the home by the [Grand Army of the Republic] in the 1880s, has been removed from the old Ward Theater because the building is untenable.” As someone who often drove or walked or rode my bike on the Hank Aaron Trail that runs through the grounds, I was intimately familiar with the tragic deterioration of many of the buildings, and in 2011 the historic district was named to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s List of Eleven Most Endangered Historic Places. As I wrote, the Home “represents the best intentions of Americans seeking to honor and protect the heroes of the Union at the same time it reflects the inability of Americans to adequately understand those veterans. My Soldiers’ Home reminds us of a time when the men who had fought and won the Civil War came to be seen as charity cases dependent on the public’s good will, rather than as heroes deserving of the country’s gratitude.”[3]

Even as the buildings continued their decline, the organization “Save the Soldiers’ Home,” leading a coalition of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Milwaukee Preservation Alliance, tried to raise money and ideas through public education. I was actually involved for a time with one of its committees. But an initial effort to get bids for preserving and redeveloping the old buildings failed, and it seemed the buildings would continue their slow, inevitable decline.

But the project gradually gained momentum behind a shrewd redevelopment plan, earning buy-in from local veterans organizations, the Veterans Administration, and the city government. After over two years of construction, in March 2021, the old main building and several other of the smaller nineteenth century buildings (the headquarters and a few duplexes built for officers of the NHDVS) opened as housing for homeless veterans! Altogether, the $44 million project created 101 housing units, with a mix of single bedrooms with shared living spaces to one to three and even four-bedroom apartments. Women veterans have their own wing, and all residents have access to fitness facilities and a business center. The VA will also provide on-site support services, including counseling, sobriety maintenance, and employment assistance. The housing is meant to be permanent, not transitional or temporary; residents will pay no more than 30 per cent or their income in rent.[4]

Over 120 years ago that forgotten newspaper writer wrote this of the veterans he met in Milwaukee and the last home most would occupy: “It is a grand thing that these refuges are provided; and we honor the men who wrecked their futures in many cases to hold the republic together.” He meant it ironically, in a way, but it is a worthy ending to this Memorial Day story about new beginnings: both for a place that deserves to be remembered productively, and for the men and women who have borne our country’s more recent battles.[5]

[1] Lancaster (Wisconsin) Teller, August 11, 1898. The Iron Brigade was the only fully “western” brigade in the Army of the Potomac. Made up of the Second, Sixth, and Seventh Wisconsin, Nineteenth Indiana, and the Twenty-fourth Michigan, it fought at Antietam and Gettysburg and lost more men than any other brigade in the Union army.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “My Soldiers’ Home,” Gary Gallagher and Matt Gallman, eds., Civil War Places: Seeing the Conflict through the Eyes of Its Leading Historians (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 168, 169; “America’s Most Endangered Historic Places—Past Listings,” https://savingplaces.org/11most-past-listings#.WZA7I2eWzVM, accessed, August 13, 2017.

[4] David Walter, “Renovated Soldiers Home Almost ready for homeless Vets,” VAntage Point: Official Blog of the U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs, February 13, 2021, https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/84463/renovated-soldiers-home-almost-ready-homeless-vets/, accessed April 4, 2021.

[5] Lancaster (Wisconsin) Teller, August 11, 1898.

James Marten

James Marten is professor emeritus of history at Marquette University and a former president of the Society of Civil War Historians. He is author or editor of nearly two dozen books, including his most recent, The Sixth Wisconsin and the Long Civil War: The Biography of a Regiment (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2025).

Catherine A. Jones has won the $1,000 George and Ann Richards Prize for the best article published in The Journal of the Civil War Era in 2020. The article, “The Trials of Mary Booth and the Post-Civil War Incarceration of African American Children,” appeared in the September 2020 issue.

Catherine A. Jones has won the $1,000 George and Ann Richards Prize for the best article published in The Journal of the Civil War Era in 2020. The article, “The Trials of Mary Booth and the Post-Civil War Incarceration of African American Children,” appeared in the September 2020 issue.

It is fitting that James Brooks will introduce this special issue and its contents, since this and the parallel volume in the Western Historical Quarterly represent his hands-on editing and his wide-ranging view of intertwined histories. We thank him, WHQ editor Anne Hyde, former JCWE editor Judith Giesberg, and former JCWE associate editor Stacey Smith for bringing the two journals—and more importantly the two fields—together.

It is fitting that James Brooks will introduce this special issue and its contents, since this and the parallel volume in the Western Historical Quarterly represent his hands-on editing and his wide-ranging view of intertwined histories. We thank him, WHQ editor Anne Hyde, former JCWE editor Judith Giesberg, and former JCWE associate editor Stacey Smith for bringing the two journals—and more importantly the two fields—together. Macon Telegraph published “A Lesson from Italy,” declaring that the king of the new nation of Italy provided an example of virtue and democracy in the wake of war that the world, especially the US, would be wise to follow, and contrasted this approach with the US’s supposed course of using the excuse of war to limit white southerners’ democratic rights.

Macon Telegraph published “A Lesson from Italy,” declaring that the king of the new nation of Italy provided an example of virtue and democracy in the wake of war that the world, especially the US, would be wise to follow, and contrasted this approach with the US’s supposed course of using the excuse of war to limit white southerners’ democratic rights. As the emphasis on restoration of former Confederates’ political rights indicates, former Confederates found international comparisons particularly useful in seeking to avoid punishment or even consequences for their actions. Restriction of former Confederates’ rights, however temporary, was one such consequence that former Confederates used international comparisons to declare contrary to national unity, as had the writer in the Richmond Whig comparing Republican policies to those of Austria toward Hungary. Expansion of political rights to freedmen was another action that former Confederates interpreted as punishment, and therefore equated with tyrannical actions abroad. The Macon Telegraph declared, for example, that it had tried to demonstrate former Confederates’ willingness to unite with the North, but that Radicals rejected such peace offerings by insisting on racial equality. In the process, Republicans supposedly recreated Russia’s much-maligned oppression of Poland on American soil.

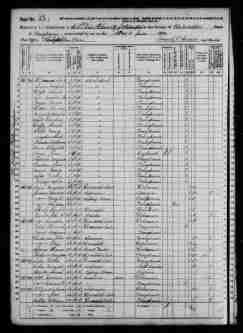

As the emphasis on restoration of former Confederates’ political rights indicates, former Confederates found international comparisons particularly useful in seeking to avoid punishment or even consequences for their actions. Restriction of former Confederates’ rights, however temporary, was one such consequence that former Confederates used international comparisons to declare contrary to national unity, as had the writer in the Richmond Whig comparing Republican policies to those of Austria toward Hungary. Expansion of political rights to freedmen was another action that former Confederates interpreted as punishment, and therefore equated with tyrannical actions abroad. The Macon Telegraph declared, for example, that it had tried to demonstrate former Confederates’ willingness to unite with the North, but that Radicals rejected such peace offerings by insisting on racial equality. In the process, Republicans supposedly recreated Russia’s much-maligned oppression of Poland on American soil. The highly bureaucratic system influenced USCT veterans’ decision to apply for a pension through the Bureau of Pensions. The lengthy and honestly daunting process involved numerous individuals listed on the application—invalid (veterans deemed, depending on the enacted pension law at a specific time, as disabled or elderly, and unable to resume working) and dependents (widow, mother, minor, sister, or father). Witnesses (including family members, employers, community members, and other veterans) were critical participants who could potentially substantiate vital information on the personal lives of an applicant. While not all applicants used lawyers, these hired individuals advocated on behalf of their client and facilitated conversations with pension agents. In the case of invalid (or veteran) cases, medical examinations could either prove or refute a veteran’s visible disability or disabilities that the veteran claimed, prior to the 1890 pension law, made him pension-eligible. All applications required extensive documentation. White male pension agents scrutinized the materials and intrusively probed into the claims of the applicants, listed dependents, and witnesses. Many applicants had to provide information on their employment history, relationship to the veteran, medical ailments, dates of births, financial standing, character assessment by community members and agents, and sometimes sexual history as part of the process, which could take years, if not decades.

The highly bureaucratic system influenced USCT veterans’ decision to apply for a pension through the Bureau of Pensions. The lengthy and honestly daunting process involved numerous individuals listed on the application—invalid (veterans deemed, depending on the enacted pension law at a specific time, as disabled or elderly, and unable to resume working) and dependents (widow, mother, minor, sister, or father). Witnesses (including family members, employers, community members, and other veterans) were critical participants who could potentially substantiate vital information on the personal lives of an applicant. While not all applicants used lawyers, these hired individuals advocated on behalf of their client and facilitated conversations with pension agents. In the case of invalid (or veteran) cases, medical examinations could either prove or refute a veteran’s visible disability or disabilities that the veteran claimed, prior to the 1890 pension law, made him pension-eligible. All applications required extensive documentation. White male pension agents scrutinized the materials and intrusively probed into the claims of the applicants, listed dependents, and witnesses. Many applicants had to provide information on their employment history, relationship to the veteran, medical ailments, dates of births, financial standing, character assessment by community members and agents, and sometimes sexual history as part of the process, which could take years, if not decades.