Spatial Roots, Lawsuits, and Leisurely Pursuits: A SHA 2018 Recap

Morning panels on the last day of conferences can be difficult. But a Sunday morning panel at the SHA 2018 Annual Meeting offered refreshing perspectives on Reconstruction Studies scholarship. The three panelists of “Emancipationist Memory and Radical Dreams of Freedom: New Directions in African American History of the Reconstruction Era” epitomized the benefits of closing out a wonderful conference. With the sesquicentennial celebration underway, Nicole Myers Turner (Virginia Commonwealth University), Giuliana Perrone (UC-Santa Barbara), and Caitlin Verboon (Virginia Tech) demonstrate that Reconstruction Studies as a field offers critical questions and insights for the current political moment. This post attempts to answer the broad questions raised during Carol Emberton’s comments–where does their work fit in the current historiography? Which specific conversations are the authors entering?

Nicole Myers Turner’s paper explores the role of black Baptist networks in shaping African American political identity in Virginia. Her paper enters the scholarly conversations defined by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, James M. Washington, and others for understanding postwar African American religious developments, and it extends the Reconstruction-era chronological frame by including the Readjusters as defined by Jane Dailey and others.[1]

By digitally mapping black Baptist networks in Virginia, Turner renders visible the spatial roots of African American Baptists’ political influence. This fresh perspective reveals how religious networks converged with political gains. She cites the petition of Virginia students who despite attending Howard University, expected William Mahone, former Confederate general and Readjuster political leader, to provide a patronage position to their African American professor as a condition of their electoral support. By 1883, these African American Baptists held political sway and applied their networks accordingly for the extension of Reconstruction-era patronage.

Though not fully appreciating the breadth and depth of these spatial roots, Mahone tapped into Baptist networks by using a circular to canvass for their support. Here, Turner’s use of digital mapping reveals that the robust African American religious networks replicated the political networks necessary for Readjuster success. Mahone’s lack of appreciation of these networks was exposed during John Mercer Langston’s 1888 campaign to become U.S. House representative of the Virginia Congressional Fourth district. Although initially losing to Edward Venable, Langston successfully contested the election and was seated in 1889. His success revealed the strength of black churches and political networks in drawing on older efforts.

The combination of the Howard University students’ petition, Mahone’s canvas circular, and Langston’s successful U.S. House campaign convincingly shows that the “Black Baptist Church held the soul of the nation.” Based on this brief paper, her forthcoming larger work on black Baptist education, and political and religious networks, will definitely be a valuable addition to Reconstruction Studies.

Giuliana Perrone’s “Claiming Freedom: Black Litigants in Post-Emancipation Southern Courts” enters the conversation recently shaped by Sharon Romeo, Melissa Milewski, and Martha Jones.[2] She differs from these legal scholars by seeing judicial opinions as evidence of the preservation and stretching of jurisprudence and not as a revolutionary Reconstruction-era gain. Rather, Perrone emphasizes the role of judges and the burden placed on African American litigants by examining three specific cases of apprenticeship, marriage, and child legitimacy.

As noted by Wilma King and Catherine Jones, former Confederate states employed its apprenticeship laws for restricting African American parental claims and often directly affecting the most vulnerable members of their families.[3] The 1867 Ambrose v. Russel ruling eviscerated portions but not all of North Carolina apprenticeship laws. Perone contends that the ruling merely stretched–without radically dismantling–antebellum jurisprudence. In other words, the Reconstruction Era judiciary extended due process previously afforded to free black North Carolinians to include newly freed African Americans. This is a novel interpretation but one that needs further clarification as suggested by Emberton’s insightful question–“what would a revolutionary judicial opinion look like in this specific example?” Since judicial opinions did not exist in a vacuum, her paper, even if not intentionally, raises another question for future interrogation: what was the lived consequences of jurisprudence on post-emancipation African American children whose lives remained bound to adult decisions, whether their parents, former enslavers, lawyers, and/or appellate judges? Here Perrone’s larger work has the opportunity to bridge legal studies and childhood studies in this example.

The next two examples demonstrate the promise of Perrone’s larger work. The second example explored a legitimacy case between an African American widow and her white husband’s extended family in a Shreveport, Louisiana estate dispute. Despite taking precautions of a postwar Catholic Church marriage and baptism of children born before emancipation, her husband’s extended family contested her and her children’s inheritance rights. The judicial opinion cited the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and Louisiana law sanctioning interracial marriage as eliminating previous disabilities. Thus, the judge applied both federal and state law evenly and not in a revolutionary act. In this regard, Perrone agrees with Mileweski who emphasizes the role of judges in shaping the courts, which now included former enslaved individuals as both litigants and appellants for the defining of postwar citizenship rights. Her last example explored a Kentucky ruling where Julia Martin’s child was ruled as illegitimate because her marriage did not survive the transition into freedom. This continuing disability affected both mother and child and placed an incredible burden on the Martin household. Overall, Perrone’s paper demonstrates the need for further contemplation over the radical (or not) of the Reconstruction-era judiciary.

Lastly, Caitlin Verboon explores the circus and leisure activities as tools for defining and redefining notions of race, freedom, and citizenship in “Public Leisure: Black and White Social Life in the Reconstruction-Era South.” Circuses were open to all crowds, including vice along the edges. She shows how “pleasure was political” and deepens the work of David Goldberg and Victoria Wolcott.[4]

The circus functioned as an important site for making and remaking postwar society. Some southern newspapers criticized African Americans for their lack of thrift by spending money at the circus and therefore demonstrating their unfitness for freedom. Some white southerners even employed African Americans’ enjoyment of the circus as justification for denying them the right to participate in state militias. Simply put, the circus allowed for the advancement of white supremacy. In contrast, African Americans actively defended going to the circus as a right of citizenship. Here, they claimed the circus as an emancipatory space and in turn, leisure as a right of citizenship. Some even appealed directly to the Freedmen’s Bureau when their admission was denied. Foretelling later African American struggles for leisurely pursuits, Verboon is astute in her analysis.

Verboon concludes with a discussion of racial incident at a Baton Rouge circus show to demonstrate the competing arguments for and against a racially-inclusive democratic society. By focusing on one racial incident depicted in three different accounts, she sheds light onto how vice occurring at the edges, and how the murder of a circus performer galvanized opposition toward the social-leveling possibilities found at the circus. After taking panel attendees to the circus, her paper raises questions about which other sites of leisure provided similar opportunities and even the role of African Americans’ politics of respectability in either advancing or stifling leisure as a right of citizenship during and after Reconstruction.

By exploring spatial roots, lawsuits, and leisurely pursuits, these three papers demonstrate the rewards of expanding the temporal, spatial, and intersectional boundaries of Reconstruction Studies as a field. Turner, Perrone, and Verboon not only engage with “unfamiliar and uncomfortable ground,” but in so doing, remind us that the legacy of the Reconstruction Era matters politically, legally, and socially in the present moment.[5] These forthcoming larger projects will add both vitality and depth of the current field.

[1] Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992); James Melvin Washington, Frustrated Fellowship: The Black Baptist Quest for Social Power (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1986); Jane Dailey, Before Jim Crow: The Politics of Race in Postemancipation Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

[2] Sharon Romeo, Gender and the Jubilee: Black Freedom and the Reconstruction of Citizenship in Civil War Missouri (Athens: University of Georgia, 2016); Melissa Milewski, Litigating Across the Color Line: Civil Cases Between Black and White Southerners from the End of Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); Martha S. Jones, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[3] Wilma King, Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteen Century America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995); Catherine A. Jones, Intimate Reconstructions: Children in Postemancipation Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015).

[4] David E. Goldberg, The Retreats of Reconstruction: Race, Leisure, and the Politics of Segregation at the New Jersey Shore, 1865-1920 (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017); Victoria W. Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

[5] Luke E. Harlow, “Introduction: The Future of Reconstruction Studies,” Journal of Civil War Era 7 (March 2017): 4-5.

Hilary N. Green

Hilary N. Green is the James B. Duke Professor of Africana Studies at Davidson College. She previously worked in the Department of Gender and Race Studies at the University of Alabama where she developed the Hallowed Grounds Project. She earned her M.A. in History from Tufts University in 2003, and Ph.D. in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2010. Her research and teaching interests include the intersections of race, class, and gender in African American history, the American Civil War, Reconstruction, as well as Civil War memory, African American education, and the Black Atlantic. She is the author of Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1890 (Fordham, 2016).

Today we share an interview with Bradley Proctor, who published an article in our September 2018 issue,

Today we share an interview with Bradley Proctor, who published an article in our September 2018 issue,

In this imaginative and deeply moving book, George Saunders has re-envisioned the moment when President Lincoln’s eleven-year-old son Willie died, in February 1862, ten months into the Civil War. Saunders’ novel is an odd and unconventional book, composed of fragments of actual historical writing and fictionalized historical passages, along with the musings of individuals who have died and now inhabit the cemetery where Willie’s body has been interred. This is the “Bardo” of the book’s title – a sort of in-between place, poised between the land of the living and a more definitive afterlife – and the book’s central premise involves the struggle to get Willie, and his father, to fully accept death so that Willie can leave this disturbing transitional world.

In this imaginative and deeply moving book, George Saunders has re-envisioned the moment when President Lincoln’s eleven-year-old son Willie died, in February 1862, ten months into the Civil War. Saunders’ novel is an odd and unconventional book, composed of fragments of actual historical writing and fictionalized historical passages, along with the musings of individuals who have died and now inhabit the cemetery where Willie’s body has been interred. This is the “Bardo” of the book’s title – a sort of in-between place, poised between the land of the living and a more definitive afterlife – and the book’s central premise involves the struggle to get Willie, and his father, to fully accept death so that Willie can leave this disturbing transitional world.

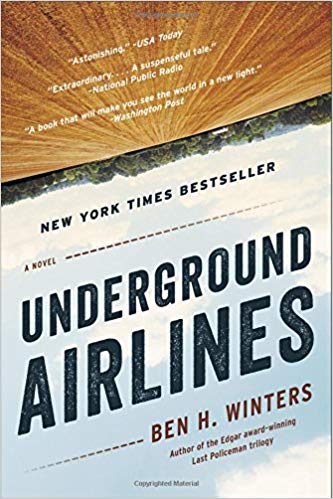

Because most are poorly-plotted, barely-disguised apologies for the Lost Cause, many historians have a low tolerance for “alternative histories” of the Civil War. Whether in the form of Confederate memorials like Silent Sam or Harry Turtledove novels, folks love to fantasize about what the United States would have been like if the South had won. Missing from most of these alternative histories is any mention of slavery, or when it does appear, as in Turtledove’s 1992 novel The Guns of the South, it appears as a foil to highlight the noble characteristics of Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee. However, a promising new alternative history, which may be of interest to scholars and history buffs alike, breaks this mold and makes slavery central to its narrative.

Because most are poorly-plotted, barely-disguised apologies for the Lost Cause, many historians have a low tolerance for “alternative histories” of the Civil War. Whether in the form of Confederate memorials like Silent Sam or Harry Turtledove novels, folks love to fantasize about what the United States would have been like if the South had won. Missing from most of these alternative histories is any mention of slavery, or when it does appear, as in Turtledove’s 1992 novel The Guns of the South, it appears as a foil to highlight the noble characteristics of Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee. However, a promising new alternative history, which may be of interest to scholars and history buffs alike, breaks this mold and makes slavery central to its narrative.

In 1997, Patrick Chamoiseau, author of a dozen works about his native home of Martinique, published Slave Old Man in Creole and French. Now in 2018, the beautiful English translation by Linda Coverdale makes this short yet sophisticated novel accessible to American audiences. Set “in slavery times in the sugar isles,” or the early nineteenth-century French West Indies, the novel illustrates the raw operation of plantation slavery in a place that white southerners both coveted and critiqued in the Civil War era. The French West Indies were strategic islands in a broader world system of slavery and sugar. As Matthew Karp explains, southern slaveholders kept a watchful eye on these islands as part of a broad, “hemispheric defense of slavery.” After the French abolished slavery on the islands in 1848, they explicitly argued that economic decline on the islands was the fault of disorder that emancipation wrought.

In 1997, Patrick Chamoiseau, author of a dozen works about his native home of Martinique, published Slave Old Man in Creole and French. Now in 2018, the beautiful English translation by Linda Coverdale makes this short yet sophisticated novel accessible to American audiences. Set “in slavery times in the sugar isles,” or the early nineteenth-century French West Indies, the novel illustrates the raw operation of plantation slavery in a place that white southerners both coveted and critiqued in the Civil War era. The French West Indies were strategic islands in a broader world system of slavery and sugar. As Matthew Karp explains, southern slaveholders kept a watchful eye on these islands as part of a broad, “hemispheric defense of slavery.” After the French abolished slavery on the islands in 1848, they explicitly argued that economic decline on the islands was the fault of disorder that emancipation wrought. The cover of Charles Frazier’s Varina: A Novel identifies its author as the “bestselling author of Cold Mountain.” When Cold Mountain, his first Civil War novel, appeared in 1997, it stayed on the New York Times list for over a year and won him the National Book Award. The star-studded film in 2003 earned $175 million worldwide, and Renée Zellweger collected an Oscar for her performance as Ruby Thewes. The relationship between Ada Monroe and Ruby Thewes was a nuanced counterpoint to Ada’s love story with Inman, and it emerged as a paean to female friendship and to wartime survival.

The cover of Charles Frazier’s Varina: A Novel identifies its author as the “bestselling author of Cold Mountain.” When Cold Mountain, his first Civil War novel, appeared in 1997, it stayed on the New York Times list for over a year and won him the National Book Award. The star-studded film in 2003 earned $175 million worldwide, and Renée Zellweger collected an Oscar for her performance as Ruby Thewes. The relationship between Ada Monroe and Ruby Thewes was a nuanced counterpoint to Ada’s love story with Inman, and it emerged as a paean to female friendship and to wartime survival.